El Ciudadano

Original article: Radiografía al ahorro adicional (Glosa 9) o cómo las familias y el Estado sostienen el alza del precio del suelo para la vivienda

Collaboration with El Pincoyazo

Land Prices: The Main Barrier to Social Housing Construction

The subsidies provided by the Housing and Urban Development Services (SERVIU) for housing committees set a maximum limit of 300 UF for land purchases to avoid underfunding other areas, such as actual construction. Consequently, if the land price exceeds this limit, the plot is disregarded.

For many years, this policy has caused most social housing projects to be built on the outskirts of the city, with poor access to public services—not due to a lack of available land. Occasionally, the state has implemented additional subsidies to bridge this gap, but ultimately, they have been absorbed by the speculation practiced by those controlling land in the city.

In other words, failing to curb land price speculation and instead subsidizing the gap has been the state’s approach to making some projects feasible, such as the 61 examined in this research.

The problem? This comes at the expense of further impoverishing family and government finances, excludes the poorest sectors without savings capacity, and by not addressing the root cause, it becomes an incentive for companies to raise land prices, worsening the crisis.

The Additional Savings Provision 9

Rather than addressing land price speculation, during Piñera’s second term, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development (MINVU) created a provision—an annual budgetary spending measure—allowing SERVIU to increase subsidy amounts for purchasing more expensive land, provided that families contribute to the increase with greater savings.

This policy (initially provision 12, then provision 10, and up until 2025, provision 9) not only continued under Boric’s current government but intensified.

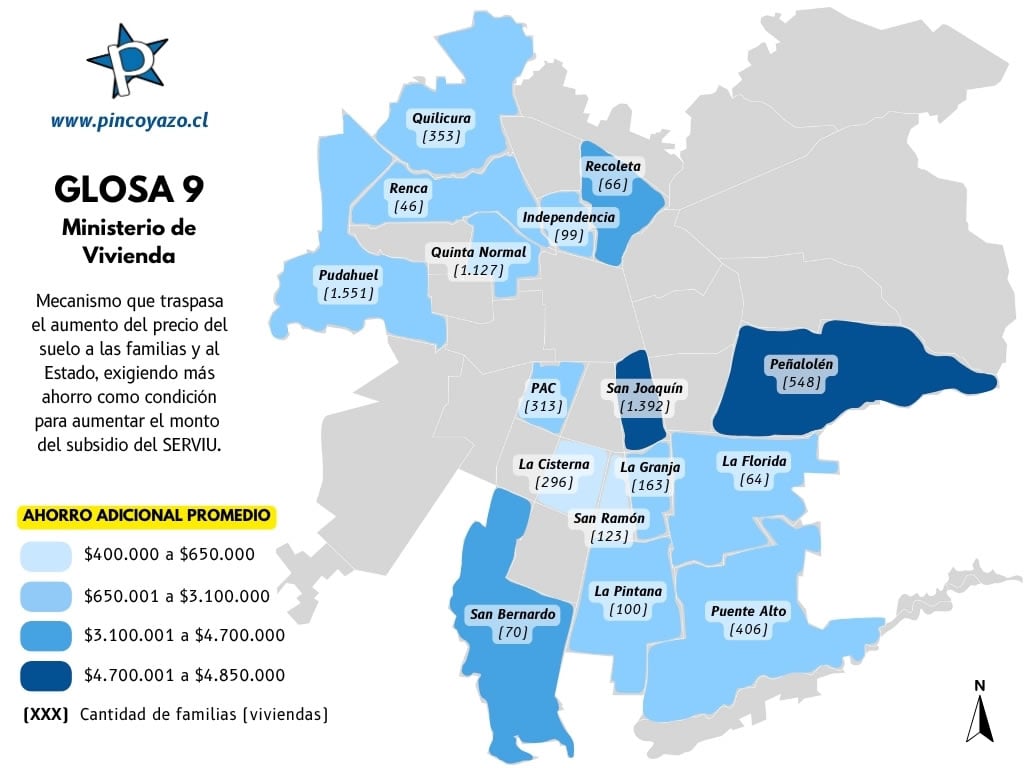

According to data from MINVU, compiled by El Pincoyazo, between April 2024 and April 2025, 61 projects were approved under this provision, broken down as follows:

- Overall, the regular subsidies for these 61 projects (8,723 homes) could cover approximately $96 billion pesos for the 61 plots (estimating a maximum of 300 UF per subsidy for land). However, as landowners sought higher profits and held absolute power to set prices, they ended up receiving an additional $67 billion (+70%), with 14% coming from increased family savings and 86% from a rise in state subsidies, on average.

- The nearly 9,000 families that applied through this channel had to provide an average of $2.5 million in additional savings specifically to cover the land price, with some projects requiring averages exceeding $6 million pesos (families’ savings varied depending on their status in the Social Registry of Households).

- The $67 billion allocated for land not only represents a way to sustain private profits but also deepens the housing access crisis, as it encourages price hikes and results in billions fewer available to address the need.

- This increase in land costs means that the average cost of social housing through regular channels, approximately $47 million, has risen to $55 million with the current provision 9, with the entire difference going straight to the landowner’s pockets. This estimate maintains the same actual construction costs noted in these projects, which vary by commune and region.

Check here for detailed cost breakdowns of the 61 projects approved under provision 9

Average Additional Savings by Commune for Projects Approved by SERVIU RM via Provision 9 (2024-2025)

The Group Patio Land in Peñalolén

In many cases, landowners acquire plots to inflate their prices, exploiting the need for land and pressuring for higher prices, often without any investment for years, merely capturing the added value that land may gain from improvements made by other entities, such as when a metro station is built nearby or other services are developed due to state investment.

Among the highest-priced land purchases recorded by SERVIU is for the housing project Quebrada de Macul in Peñalolén (288 homes), benefiting none other than Group Patio, which during Piñera’s second term was aided by lobbyist Luis Hermosilla to expedite the transfers of three plots valued at $10.372 billion, according to information from CIPER.

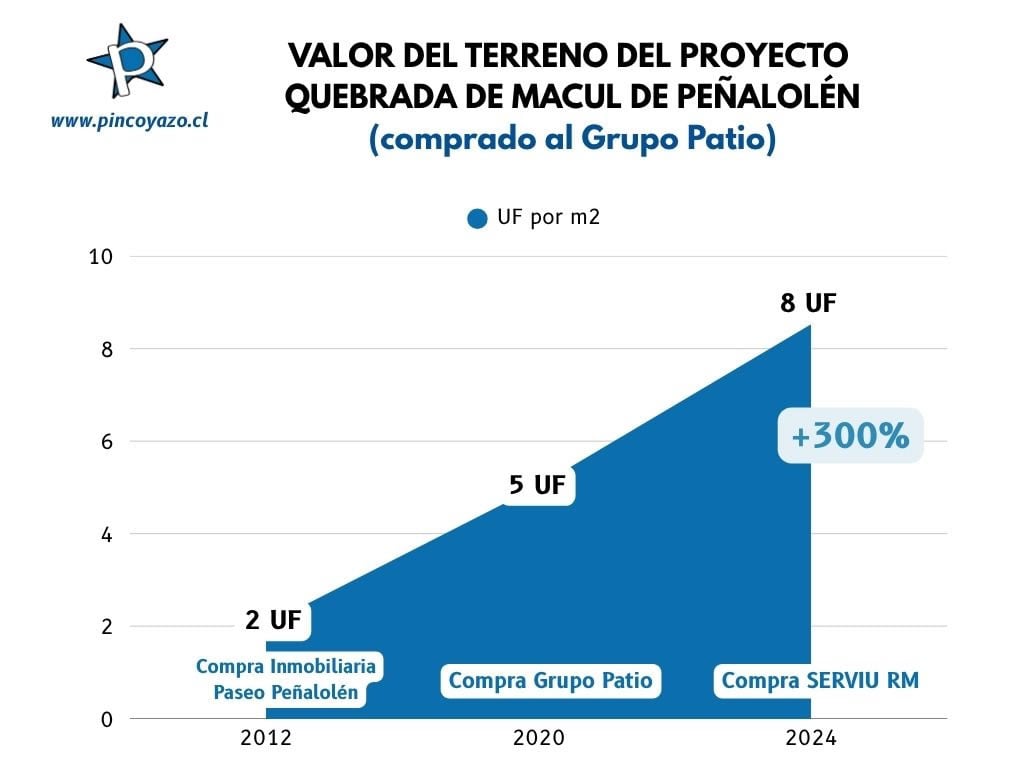

El Pincoyazo investigated the records of the last three transactions of the land purchased by SERVIU from Grupo Patio, identifying a 300% increase in its purchase value between 2012 and 2024, detailed as follows:

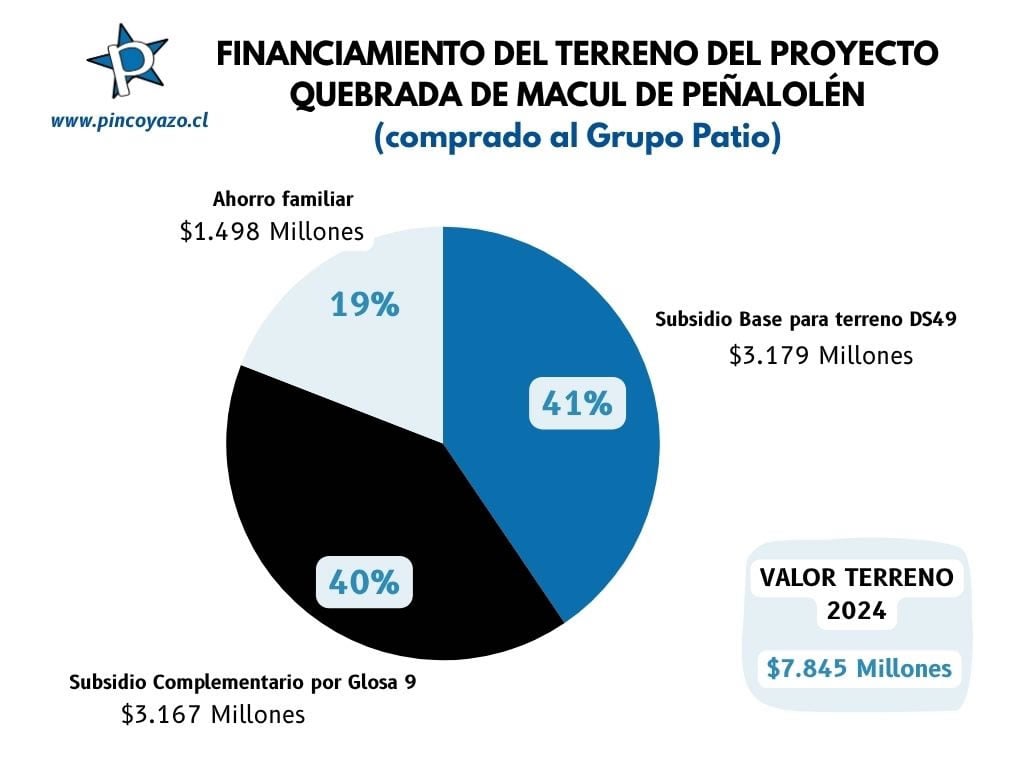

- In 2024, SERVIU acquired the land (2.6 hectares) for $7.845 billion pesos for the 288 families involved in the project (8 UF per m2).

- In 2020, this same land was acquired by Grupo Patio for 5 UF per m2 (prior to its subdivision). This means that in just four years, the undeveloped land generated a profit of $3.110 billion, merely by reserving and mediating the transfer.

- In 2012, the Inmobiliaria Paseo Peñalolén owned by the Saieh Guzmán family purchased the land from Sociedad Inmobiliaria Mario Nervi and Compañía Limitada for a value of 2 UF per m2, netting a 150% profit on the original purchase price in just 8 years without any further investment ($9.085 billion at current value for all 7.5 hectares before subdivision). Notably, in 1987, the same land was valued at $4 million, as documented in the deed.

This case, where land value increased by 300% in 12 years despite no real enhancement by the owner, such as urbanization, exemplifies a broader trend within the neoliberal city—large capital reserves portions of the city, pressures to increase prices, and thus accumulates wealth at the expense of families and communal resources.

Check the land deeds here (2012, 2020, and 2024)

After the Hermosilla case erupted in 2023, which involved the Jalaff brothers—partners of Grupo Patio as beneficiaries of false invoices—in 2024, changes in ownership occurred, with main shareholders including Paola Luksic and Óscar Lería (26% each), Eduardo Elberg (26%), Guillermo Harding (20%), and Gabriela Luksic (15%).

Thus, with no authority to impose limits on land prices, speculation is covered by more public resources and an impoverishment of families without homes, who in this case had to increase their savings by an average of $5.2 million pesos to meet the expected profits of Grupo Patio.

The Carrascal Land in Quinta Normal

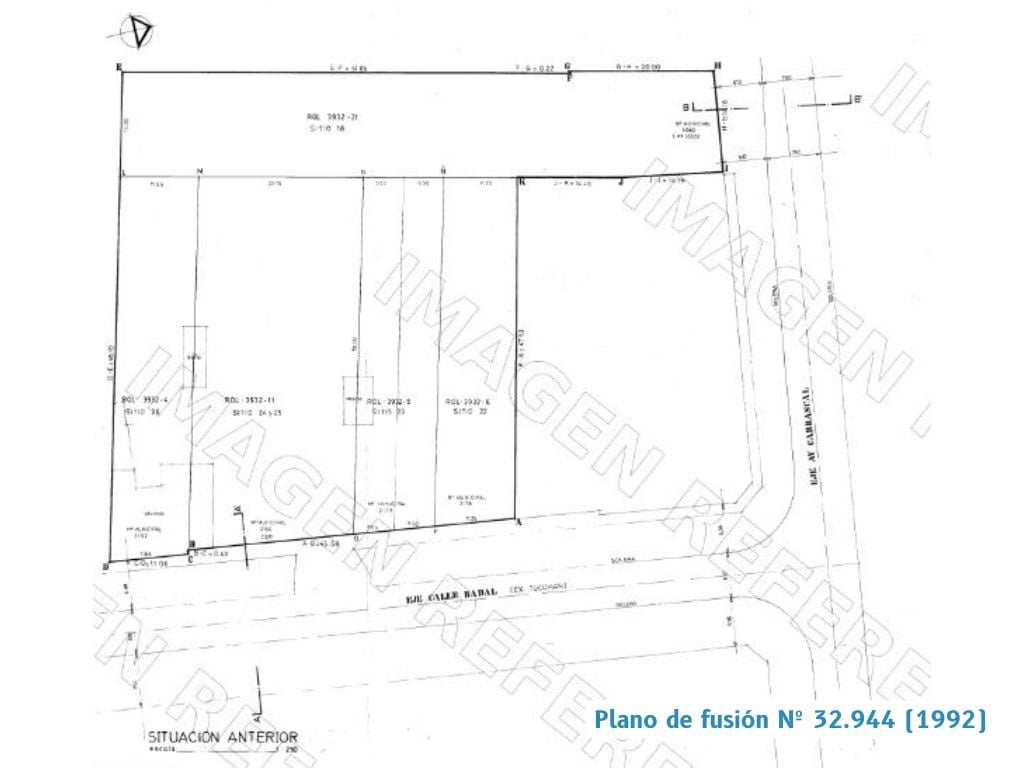

Another case examined in this research was the Carrascal land project in Quinta Normal for 139 homes, situated in a well-located area near the municipal government. The transaction history is as follows:

- In 2005, Banco Santander-Chile notes a payment of 2,690 UF for the 0.4 hectares encompassing all the land before it was merged, located at Calle Radal 2166, which amounts to 0.67 UF per m2, equivalent to $106 million in current value.

- Then, in December 2009, Oscar Azócar y Compañía Limitada paid Banco Santander-Chile 8,890 UF for all the plots (2.2 UF per m2, equating to $351 million in current value) before merging into the current plot. The strategy? Not to produce anything, but merely wait for the housing crisis to escalate.

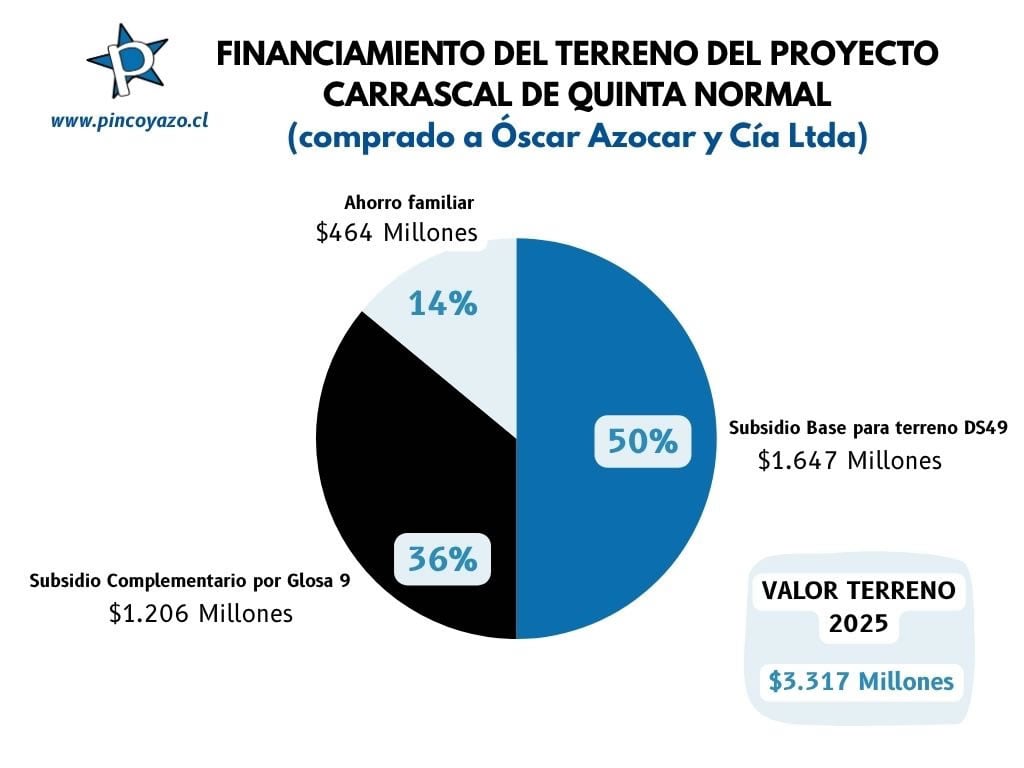

- In February 2025, SERVIU signed a purchase agreement for 83,985 UF for the same 0.4 hectares (21 UF per m2, translating to $3.317 billion) to build 139 homes. This way, the intermediary company pocketed $2.966 billion for reserving the land for 15 years.

To facilitate the purchase of this land, SERVIU had to increase the subsidy to 72,227 UF ($2.853 billion), and families contributed an additional 11,758 UF ($464 million). This meant that, on average, the 139 families had to increase their savings by $3.3 million.

Payment for Land with SERVIU Advances

According to Provision 6 of the same MINVU 2025 budget, construction companies or sponsoring entities can request a loan from SERVIU to acquire land at a 0% interest rate, repayable within three years.

In summary, this means that in addition to financing speculative costs through more family savings and state subsidies, the private company responsible for managing and constructing the project can cover land expenses with an advance provided by SERVIU.

While this is added to the final subsidy amount, it represents a diminished availability of public resources for constructing more homes or improving their quality, prioritizing providing fresh money to the private sector, which doesn’t bear project risks (the state does) nor must deduct a percentage of its profits to a bank.

The only ministry in Chile acting as a bank through these mechanisms is the Ministry of Housing, which is an anomaly and a completely inefficient public policy design to achieve its supposed goals of ensuring access to housing for those who cannot do so through market means.

Covert Displacement

Proponents of the current provision 9 argue that it allows families to access land within their own communities or nearby, which is true. The question is, at what cost and for whom?

Daniela Ocaranza is a leader of the Pachamama project, which groups 44 families in Peñalolén who, on average, had to increase their savings by $3.4 million to secure land in the commune, despite the presence of dozens of hectares of unused land reserved for future private projects, trapped by speculation, such as Viña Cousiño.

When the committee was presented with the option of increasing savings, Daniela mentioned, “It was very hard for many since a lot of the families were out of work and facing very complex conditions. Our project involves 44 families, 12 of whom are seniors and household workers who also have responsibilities for minors. Many families turned to loans from friends and family, and only 3 or 4 were able to secure a bank loan, while a few managed to do so with the help of savings groups.”

Regarding housing policy in Chile, she states, “As long as we don’t understand that housing must be a right, like education and health, we will always be in crisis. The state today lacks the muscle to tackle the housing crisis, neither as a sponsoring entity nor as a constructor; they are not capable.”

Read here “Lo Hermida for the Right to Decent Housing”

By requiring additional savings often amounting to millions, projects approved under provision 9 automatically exclude segments of the population unable to save or go into debt for three, five, or even eight million, resulting in continued overcrowding, relocation to camps, or persistently high rents consuming a significant portion of their salaries.

Discussion on the 2026 Budget

Currently, in the discussion of the 2026 MINVU budget, the Budget Directorate of the Ministry of Finance questioned the continued extension of provision 9, focusing on procedural rather than substantive issues. They argue that it is inappropriate to allocate expenses that are intended to be temporary under provisions designed for such purposes.

This is why the budget presented by the government does not include this provision for 2026, prompting pushback from some government legislators in districts where housing committees were created specifically to advance their projects under this provision.

In some cases, these processes have been initiated by municipalities through their sponsoring entities, and if the provision is not renewed, these projects could be left in limbo unless SERVIU conjures up another subsidy to fill the gap.

As of this research’s publication, the decision regarding the reinstatement of provision 9 in the budget remained pending, under the agreement that next year its inclusion in DS49 would be discussed; however, given the neoliberal housing policy consensus across all sectors in Congress, it is likely to extend without anyone suggesting the need to overcome it.

On October 25, committees from the Movimiento Solidario Vida Digna held marches in the communes of Huechuraba, San Joaquín, and San Ramón to demand the acceleration of their projects and changes to housing policy.

Regarding provision 9, Vida Digna expresses a critical viewpoint. “The problem with provision 9 is that instead of curbing land price speculation, which even the minister acknowledges as a cause of the crisis, the state has been creating mechanisms like this to reproduce the same model, making it a vicious circle,” says Simón González, the movement’s spokesperson.

Read here the statement from the Movimiento Solidario Vida Digna

The Role of Popular Organization

At the organizational level and within community networks, increasing savings to cover land prices often disrupts assemblies, as it excludes those unable to save or sustain a loan of that amount. Many families within committees resort to informal debts to reach the required savings.

Confronted with these sometimes tempting options, social leaders and housing committees need to reflect on these paths, as they may allow for possibilities while pointing to their disarticulation, often evident in changing savings conditions as the process advances, without the ability to defend themselves due to this disarticulation.

Whatever decision the committees make, it is crucial for these topics to be informed and discussed in assemblies, making them conscious because if they do not understand the role they play in the broader picture of the business that arises from this need, committees may end up being tools for the same companies to demand more resource transfers or to extend a provision endlessly to cover up issues without addressing the system and the inequality it reproduces.

La entrada Analyzing Additional Savings: How Families and the Government Sustain Rising Land Prices for Housing se publicó primero en El Ciudadano.

Ver noticias completa