Publicidad

¿Quieres publicar aquí?

Sólo contáctanos

El Ciudadano

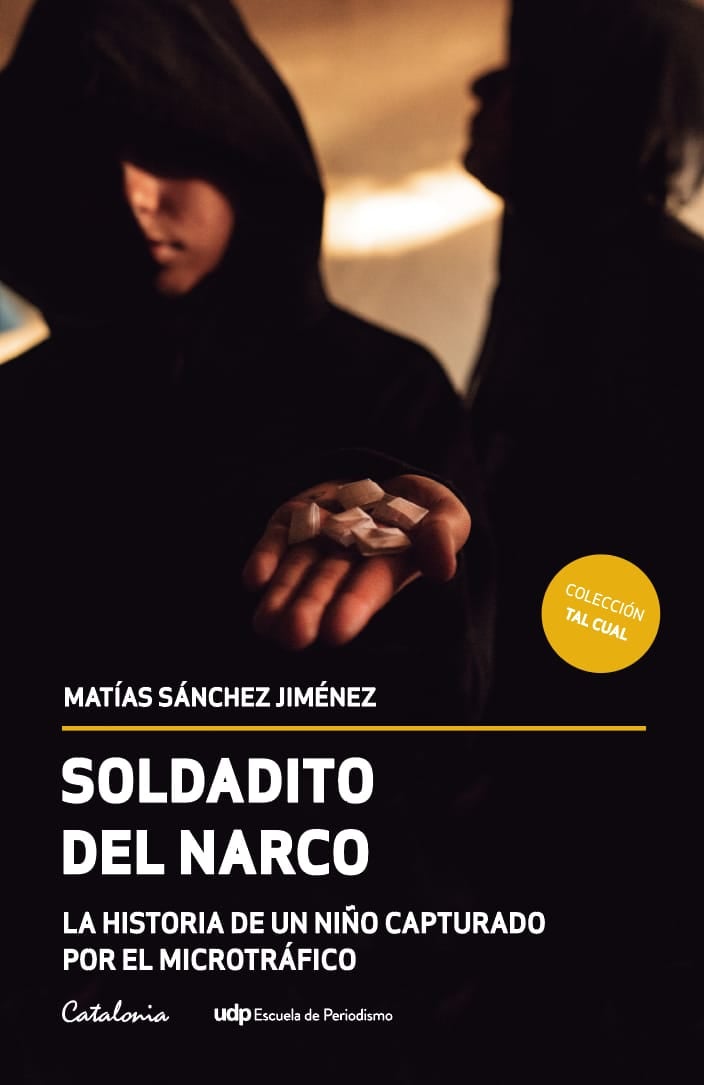

Original article: Adelanto del libro «Soldadito del narco» de Matías Sánchez Jiménez: Capítulo 5, «El Recluta»

Chapter 5 – The Recruit

In January 2015, shortly after turning thirteen and moving to his neighbor’s home, Emerson Zamorano’s lifestyle changed drastically. He remained a child but no longer wandered through the mall’s hallways. Instead, he took on a role within a drug trafficking gang in La Pincoya, led by two sisters: Johanna Morgado and Vanessa Díaz.

Carola Ortiz, his mother, witnessed this transformation firsthand. Mornings became routine for her, as she would often find her son standing at one of the entrances of El Olivillo passage. «He would stay out all night, always tasked with selling their product.» Positioned at a corner, Emerson was selling drugs. He kept paper wrap with small amounts for quick transactions in a sling hung across his chest. This role earned him around $10,000 daily. Additionally, marijuana and base paste use, along with gifts like sneakers and clothes, provided extra benefits.

—Emerson liked the life of a dealer; he hung out with other kids to smoke. Everything was handed to him — his mother recalls.

In the drug trade, soldiers rank at the lowest level of the hierarchical structure. Their responsibilities are straightforward: defend territory from rival gangs, alert others to police presence in the area, and carry and sell drugs in small quantities. These minimal tasks come with high risks to personal safety and the threat of police arrest.

In Latin America, minors as young as thirteen are often recruited by criminal groups. Gangs offer a sense of community, identity, and belonging often missing from their surroundings. They also seek the protection traffickers provide against violence and pressures experienced, frequently from their own families. Feelings of exclusion and frustration are significant factors attracting young people to gangs.

In El Olivillo, sisters Johanna Morgado and Vanessa Díaz recognized these gaps in the community. Their primary interest in recruiting minors as soldiers lay in the fact that such youths are exempt from criminal liability.

In Chile, youths aged fourteen to eighteen who commit crimes are processed under the Juvenile Criminal Responsibility Law (LRPA), which prevents them from receiving custodial sentences. Depending on the offense, they may face sanctions such as mandatory attendance at intervention and social reintegration programs. In severe cases, they may be provisionally detained in a juvenile facility. Notably, in 2023, the law was amended to include aggravating factors for using children, girls, or adolescents in drug trafficking-related crimes.

However, experts argue that such penalties are insufficient to separate minors from gangs, as even those in state protection programs remain entrenched in drug- and crime-ridden neighborhoods and often escape from detention centers to return to drug traffickers.

At the time of his recruitment, Emerson met all the criteria: he had been out of school for two years, lived in a drug-infested environment, and faced various familial deficiencies. Joining the gang presented an opportunity for advancement and a supportive community.

Jason recounts how his brother became a soldier.

—He turned into a different Emerson. He was always standing on the corner, selling. He looked unwell, strung out, sometimes sprawled on the street without shoes. He consumed a lot of base paste. I felt sorry for him, but I learned from that. I realized I never wanted to get involved in such things.

—Did you talk to him?

—No, he didn’t want to talk to me anymore. He wouldn’t come near me; he distanced himself.

—From you?

—He distanced himself from everyone.

Carola attempted to persuade her son to return home. However, the allure of drugs and gifts held him captive.

—Once he left, Emerson felt more authoritative. He treated me poorly, calling me “shut up, crazy old lady” or yelling other things. My family and I did everything we could to get him out, but we couldn’t. She would create disturbances and threaten us. We had some serious fights; they would come threatening us in groups.

—What kinds of things did you try to get your son back?

—I talked to Emerson, conversed with him, telling him to listen to the Lord.

—And with his neighbor?

—I spoke with her too, in good faith. I said, “Vanessa, look, I want to ask you a favor. Get my son out of there, keep him from coming to your house.” She responded, “No, Emerson is fine with me.” She gifted him shoes, clothes, even gave him a motorcycle. She bought my son, and he did her favors. If he didn’t, they would hit him or take away the drugs.

Carola reported her neighbor to professionals at the PEC Recoleta, where all her children remained enrolled by family court order after a report of rights violations. In April 2015, after Emerson had been living with Vanessa for four months, PEC Recoleta issued a report on the mother and her children’s situation. It details various activities organized to strengthen ties between Emerson and his siblings, including football workshops, visits to parks, swimming pools, and the zoo. The documentation was sent once again to the Court of Protective Measures.

“Emerson did not attend any of the activities he was invited to during January and February. During home visits, it was also not possible to connect with him. This was due to the fact that the young man was living with a neighbor who is involved in drug trafficking. Upon attempting to contact him in that space, the young man would flee from the professionals. His mother states she has tried to bring him back without much success.”

Among its conclusions, PEC Recoleta recommended keeping Carola and her children in the program. It also called for “urgent evaluation for detoxification of Emerson at the Roberto del Río Children’s Hospital.” In response to the report against Vanessa, the family court requested a search order from the Sexual Crimes and Minors Investigation Brigade (Brisexme) of the Criminal Investigation Police. Emerson’s admission to the hospital never materialized.

At the beginning of June, PEC Recoleta sent another report to Judge Jessica Arenas. It reiterated that Emerson was at his neighbor’s house and had stopped attending school because “he opted for enrollment in the free exam modality.” The report also reiterated the complaint against Vanessa Díaz. “Coordination with community Carabineros (police) is being arranged to remove the young man from the neighbor’s home and investigate the level of consumption and/or activities in which Emerson may be utilized.”

On Tuesday, June 16, two weeks after the last report, Vanessa and Emerson voluntarily went to the family court building in Santiago. At 14:10, in Room 3 of the Protective Measures Center, Judge Paulina Roncagliolo held an unscheduled hearing in which Vanessa, twenty-seven years old, requested provisional custody of thirteen-year-old Emerson.

According to the hearing record, “the adolescent arrived on December 24, 2014, at the neighbor’s home, hungry and barefoot, with her providing a roof, unable to send him to the school he was enrolled in, Centro Educacional Huechuraba, due to the mother not providing the necessary documents. It also notes that whenever the claimant sees her son, she yells that she wants him institutionalized. The claimant wishes to obtain provisional custody of the minor, and the adolescent agrees, stating that he is fine with his neighbor.” When asked about drug use and dealing, both denied it.

After hearing them out, the judge and a technical advisor reviewed the child’s history. The system showed that Emerson had dozens of hearings for rights violations and evaluations of intervention programs that he never attended and where he failed to meet objectives. His judicial file included the latest reports from PEC Recoleta sent to the same family court, which contained allegations against Vanessa.

Given all this information, Paulina Roncagliolo granted provisional custody of Emerson to Vanessa for four months. She also decreed the child to remain in PEC Recoleta and nullified the search order from Brisexme.

According to the minutes, the entire hearing lasted ten minutes. During that time, Carola lost legal custody of her son, and the entire process occurred without her presence in court and without hearing her side.

—She lied to the judge because Emerson spent Christmas with me. At first, I didn’t understand what happened, but later everyone asked me, “Why did the judge take your child without your consent?” Not even a social worker was sent to my house to look into the case.

—Why do you think the magistrate made that decision?

—Since Emerson looked well-dressed, wearing Nike shoes, the judge saw his appearance and that was it. But she didn’t see what she had in her heart or her intentions.

La entrada Sneak Peek of «Little Narco Soldier» by Matías Sánchez Jiménez: Chapter 5, «The Recruit» se publicó primero en El Ciudadano.

Ver noticias completa